Every August, Japan slows its pace for one of the most meaningful and unifying traditions of the year – Obon.

Known as the Festival of the Dead or the Festival of Souls, Obon is a centuries-old Buddhist event that blends solemn remembrance with joyous celebration. It is a time when families welcome the spirits of their ancestors back into the world of the living, offering prayers, food, and light before guiding them safely home.

Part spiritual ritual and part cultural celebration, Obon is both deeply personal and widely communal – a tradition that continues to thrive even in modern Japan.

The Origins of Obon

Obon’s roots lie in the Buddhist Ullambana Sutra, which tells the story of the monk Maudgalyāyana, who wished to save his mother from suffering in the afterlife. Through offerings to the Buddhist community and acts of merit, he was able to release her spirit – and in turn, was instructed to perform similar rites annually for all ancestors.

Over time, this Buddhist narrative merged with Japan’s indigenous Shinto beliefs about ancestral spirits, creating a uniquely Japanese observance. The earliest recorded Obon celebrations date back more than 500 years, and many of the customs practised today still echo those early forms.

When Does Obon Take Place?

Obon is typically held in mid-August (13–16 August) in most of Japan, following the solar calendar. However, some regions such as parts of the north (e.g. Hokkaido) and Okinawa observe it in July, following the lunar calendar.

This variation means that travellers may encounter Obon festivities at slightly different times depending on the location. For many Japanese, Obon is also one of the most important homecoming periods of the year. Much like Chinese New Year or Thanksgiving, it is a time when people return to their hometowns, reunite with relatives, and honour the family’s lineage.

Preparations Before Obon

Obon is not a celebration that begins overnight – preparations are just as important as the festival days themselves. Families usually:

Clean the family altar (butsudan)

Removing dust, polishing ornaments, and arranging fresh flowers.

Offer seasonal produce

Such as cucumbers, aubergines, peaches, and grapes, often presented alongside incense and candles.

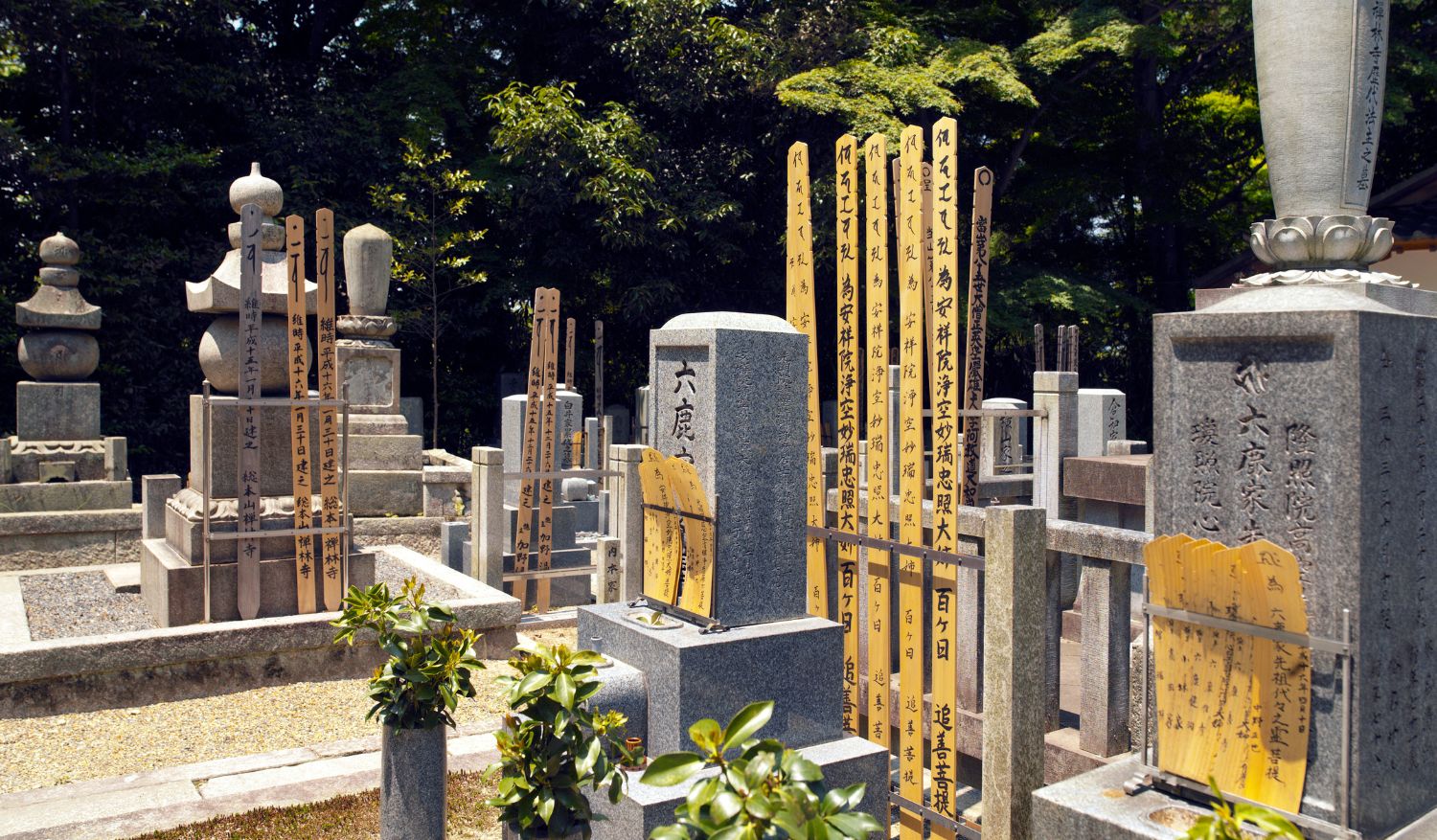

Visit and clean ancestral graves (ohakamairi)

Sweeping debris, washing the stone, and replenishing flowers and incense.

Prepare shōryōuma (spirit animals)

Small cucumber horses and aubergine cows with toothpick legs, symbolising the ancestors’ swift arrival and gentle return.

Key Rituals During Obon

Mukaebi: Welcoming fires

On the evening of 13 August, families light small fires or lanterns at the entrances of their homes to guide ancestral spirits back. These flames are said to illuminate the path from the spirit world.

Offerings and prayers

During the festival, offerings of food, drink, and sometimes the deceased’s favourite items are placed on the altar. Family members recite sutras or quietly express their gratitude and memories.

Bon Odori: The dance of remembrance

In town squares and temple courtyards, communities gather for Bon Odori, a series of traditional dances performed to the beat of taiko drums and folk songs. Each region has its own style – from the graceful steps of Gujo Odori in Gifu to the lively Awa Odori in Tokushima, which draws thousands of dancers and spectators each year.

Okuribi: Farewell fires

On the final evening, farewell fires are lit to send the spirits back to the other world. In Kyoto, the grand Gozan no Okuribi sees giant kanji characters burned into the mountainsides – an awe-inspiring spectacle visible across the city.

Tōrō nagashi: floating lanterns

In coastal or riverside towns, families release paper lanterns onto the water. These glowing vessels drift away, carrying the souls of the departed towards the horizon. The scene is serene yet deeply moving, symbolising both goodbye and continuity.

Regional Variations of Obon

Kyoto

Famous for the Gozan no Okuribi, a dramatic display of five giant bonfires shaped into characters and symbols on surrounding hills.

Tokushima

Home to Awa Odori, one of Japan’s largest dance festivals, featuring tens of thousands of dancers in colourful yukata.

Okinawa

Celebrated with eisa drumming and dancing, often performed by youth groups parading through the streets.

Hokkaido

Known for its earlier July celebration and local seafood offerings.

Food and Flavours of Obon

Like many Japanese festivals, Obon comes with its own culinary traditions. Common foods include:

Seasonal fruits

Peaches, melons, and grapes offered to the spirits.

Vegetable spirit animals

Cucumber horses and aubergine cows as symbolic transport.

Festive street foods

Yakisoba noodles, grilled squid, okonomiyaki pancakes, and kakigōri (shaved ice).

Ozen meals

Vegetarian dishes offered to the spirits, often including simmered vegetables, tofu, and rice.

Travel Tips for Experiencing Obon in Japan

Book early

Transport and accommodation fill quickly as millions travel home.

Join local festivities

Many cities welcome visitors to Bon Odori dances and night markets.

Be respectful

If visiting cemeteries or observing rituals, remain quiet and mindful.

Dress appropriately

Light cotton yukata are common and practical in summer heat.

Capture the moment mindfully

Some rituals, especially at graves or altars, are private family affairs. Always ask before photographing.

Why Obon Matters Today

In a modern, fast-moving Japan, Obon remains a cultural touchstone – a reminder that progress and tradition can coexist. It offers space for reflection, connection, and gratitude, bridging the gap between generations and keeping family heritage alive.

For visitors, it is a rare chance to witness a deeply meaningful side of Japanese life – one that blends spirituality, artistry, and human connection in equal measure. As the lanterns fade into the distance and the last drums of Bon Odori quieten, Obon leaves behind a lingering sense of warmth – a gentle reminder that the ties between the living and the departed are eternal.

For more cultural guides, head here.